Do I Dare Eat a Peach? Notes on a Prufrockian Generation

My solace on the internet this week is Stephen Colbert’s interview with Anthony Hopkins. The same terrifying man who threatened to eat our livers with a nice Chianti is older, sitting in a chair and reflecting on his life. At 88 years old, Hopkins is soft-spoken with bright blue eyes - recounts stories of sobriety, winning an Oscar at 83, and, of course, his love of poetry. Colbert, famously well-read and known to spout out Shakespeare, is no stranger to literary name-dropping, but in this specific interview, it’s Hopkins who begins reciting a poem, one I think defines every person who reads it in their 20s - my favourite version being read by Anthony Hopkins years ago.

The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock was written by T.S. Eliot in 1911, while he was studying at Oxford. Legend has it that Eliot wrote the poem, stashed it in a drawer, and forgot about it until his friend sent it to the editor of Poetry and Drama, who turned it down as “absolutely insane”. Later that year, Eliot met Ezra Pound in London, where Pound read Prufrock and immediately understood what it was, losing his mind in the process. Prufrock is a perfect example of the modernist movement - a rejection of the old structured, measured lines, mirroring chaos and disillusionment - feelings that would define life post World War One.

The war marked a cultural breaking point. Europe, long regarded as a pillar of culture and modernity, housing the archetypes of belief, religion, morality, and progress, was fractured, figuratively and literally. The old structures no longer existed, and the art that we saw of the era past felt incoherent against a new world defined by death, loss, and disillusionment. Modernism becomes a necessity as artists attempt to make sense of the fractured reality that the world has left in its wake.

Eliot’s The Waste Land has become synonymous with this point in history. The poem, along with works like Prufrock, reflects a world where meaning doesn’t really matter, identity doesn’t exist within structure, and tradition needs to be tessellated, no longer pillars. While Prufrock predates the war, it's considered an early modernist text with its characteristic emotional backbone that defines the post-war era: paralysis, self-doubt, alienation, and stagnation. By the time Eliot published The Waste Land in 1922, these anxieties were fully formed, defining the cultural zeitgeist: a landscape of cultural ruin, exhaustion, and attempts to sift through the rubble to find some sort of new meaning in the ashes. Eliot himself writes about the relationship to past art in Tradition and the Individual Talent:

In this way, Eliot’s work does not merely reflect its historical moment; it helps define it. He creates something new out of the histories that come before him, acknowledging what has been given to him as he attempts to create his own meaning throughout the fragments. His poetry gives language to a generation living in the aftermath of catastrophe, unsure of how to speak honestly in a world that no longer feels whole.

Prufrock is a special case. The poem is told in first person, following the structure of a dramatic monologue. We see the world through the narrator - a hyper-aware, self-conscious, neurotic man, constantly paralyzed by indecision and his own interiority. He is in direct conflict with himself. He obsesses over rejection, anticipating the worst at every turn, and rehearsing social encounters to talk himself out of them. He questions “Do I dare?” and “Do I dare disturb the universe?” - Any small actions can be world-ending. He observes, measuring his life incrementally as he intellectualizes his fears of intimacy.

The important element is that Prufrock is not a tragic character. He understands his insignificance. He declares that he is “no prophet” and likens himself not to Hamlet but to a minor, peripheral character. This self-minimization solidifies the modern condition Eliot captures: a narrator overwhelmed by awareness but stripped of agency, fluent in cultural reference yet unable to translate that knowledge into meaningful connection. Prufrock’s voice, restless and circular, exposes a distinctly modern form of alienation—one rooted not in isolation from society, but in overexposure to it.

Prufrock spends his time contemplating his place in society, worrying about how others perceive him, and imagining the judgments of casual acquaintances, especially at social gatherings where “the women come and go / Talking of Michelangelo.” He repeatedly hesitates, questioning whether he dares to act, “Do I dare?” and “Do I dare disturb the universe?”, illustrating the paralysis of an individual stuck in social anxiety.

Prufrock’s thoughts drift through fragmented images and allusions to Dante, Renaissance art, and biblical figures - highlighting his longing for tradition alongside his inability to connect meaningfully with others or impose order on his own life. Ultimately, the poem captures Prufrock’s psychological stasis more than any external narrative: he measures out his life “with coffee-spoons,” unable to resolve his fears or achieve the intimacy he desires, reflecting the existential uncertainty of modern life.

I could annotate the poem half to death, unpacking every allusion, every image, the fog like a cat, the mermaids, the borrowed voices - all of it. I’ve studied it, all of it. I can almost recite it as well as Sir Anthony Hopkins himself. I’ll spare you. What matters is that the feeling persists more now than it ever has.

I remember reading this poem for the first time in an AP English class as a teenager - socially awkward, suspended in the strange liminal space of being told you could be anything while being asked to decide everything. I was petrified most of the time, expected to map out my whole life at 16. I rehearsed every social interaction in advance - my answer before raising my hand, my lunch order before reaching the cafeteria counter. Prufrock felt familiar. He was the voice in my head as I navigated adulthood, weighing every decision - what classes to take, what clubs to join, what schools to apply to - until even the choice itself felt paralyzing.

And I think this is the millennial condition - we lived through constant unprecedented times - especially now as we try to navigate a world that feels uncomfortably closer to 1942 than 2026. We turn to history and to art, and we try to make sense of what we see in front of us, searching for patterns as we create meaning. Our lives are shaped by the promise that if we studied hard enough, we would be rewarded with stability - homes, family and security. A future that resembles the one that we sold. Instead, we carry a constant feeling of failure, even if we as individuals are not ultimately to blame - we are anxiously falling behind.

As we hustle to survive, society becomes increasingly isolated. We watch one another construct aspirational narratives online while privately falling behind. We retreat inward, overthinking, people-pleasing our way through nine-to-five jobs, keeping our nervous systems locked in fight or flight. Like Prufrock, we are acutely aware - endlessly reflective - and yet strangely paralyzed.

We are Prufrockian as a generation. Trapped as we measure our lives out in coffee spoons, retreating to nostalgia for comfort - the last time things made sense. I know, personally and as of late, I wear my hoodies and my Chuck Taylors, I listen to Broken Social Scene and Bombay Bicycle Club, and I too turn back and descend the stair - and I am 16 all over again. This is the last time I felt like the world, my world, makes sense. It’s why everything is Summer 2016 again now that Fetty Wap is out of jail; it’s for this same reason that we search for meaning in the rubble of years past as we make something new.

Watching Hopkins recite this poem now, at 88, decades removed from Prufrock’s first conception by a young Eliot, holds a different weight. What was once laden with youthful anxiety is now heavier and quieter. We’re growing up and growing older. We are living lives with awareness, hesitation, and the knowledge that time passes whether we want it to or not. In Hopkins’ voice, Prufrock isn’t a man afraid to act, but instead an older man reflecting on all the moments he might have disturbed the universe - or was too scared to. The poem ages with us as we reflect on the lives we’ve led, and the narratives we construct of the ruins of our past.

And this is why Prufrock is still taught in school. It does not promise resolution or release. Instead, offers recognition. Eliot gives us a skeleton for uncertainty and self-consciousness. He allows us to understand that paralysis can come from seeing too clearly in a world that demands certainty and confidence. A century later, we are still living inside that tension and still rehearsing our lives before stepping into them.

“I grow old… I grow old…” Prufrock tells us, adjusting the cuffs of his trousers, still wondering if he dares. And somehow, impossibly, he is still talking about us.

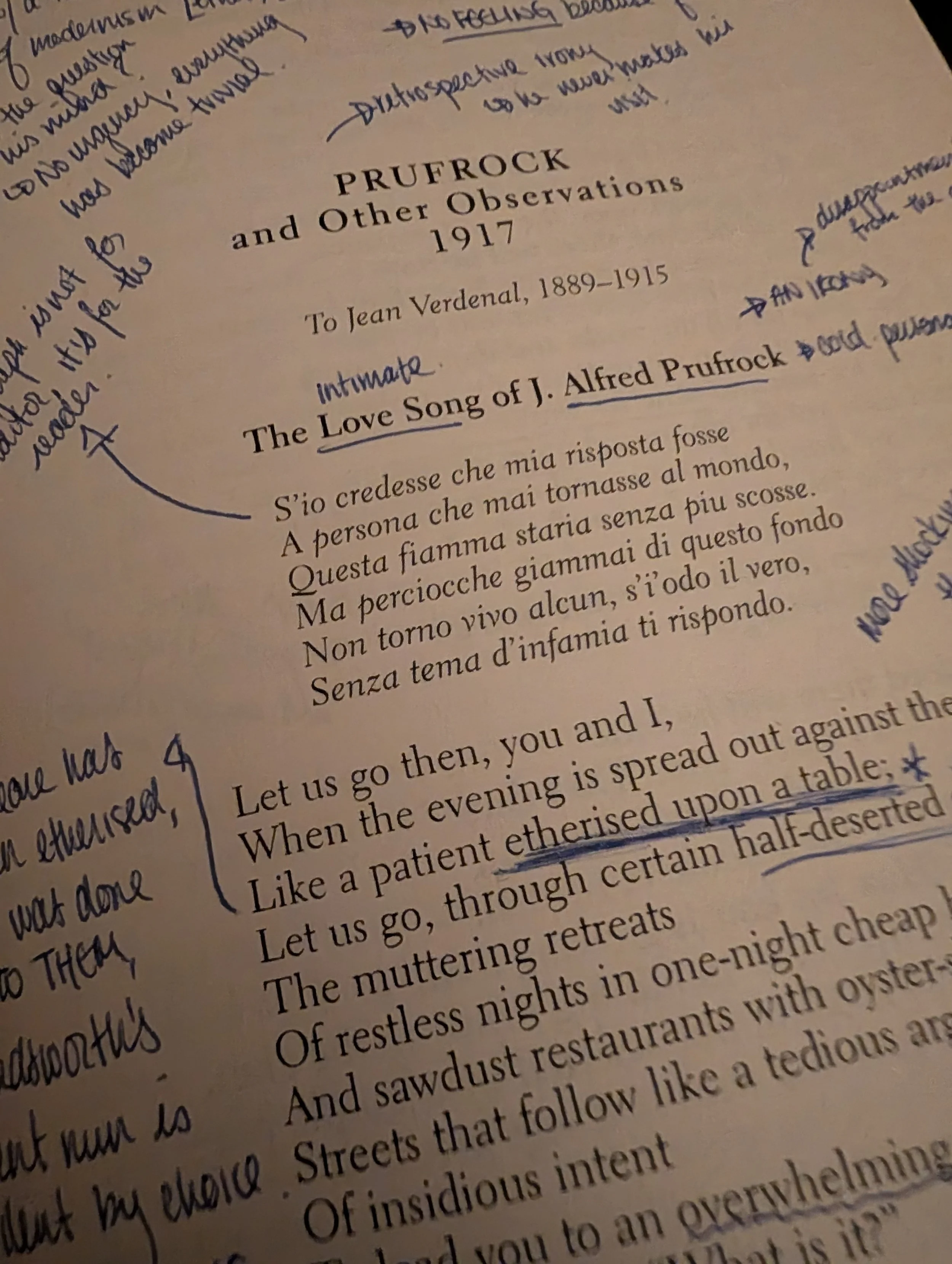

My copy of Prufrock from high school, circa 2008.