"Where TF is the rest of your arms?": Tweets from the San Andreas Fault Line and other Distractions

I’ve been reading this book recently: Amusing Ourselves to Death by Neil Postman. It was written in 1985 about what television is doing to our brains — little did Postman realize he’d end up sounding like a soothsayer. Right from the get-go, in the foreword, he makes a bold claim. The Orwellian dystopian future we think we’re living in when we look at the news isn’t actually the dystopia that feels accurate in 2026. In fact, Aldous Huxley was more accurate in Brave New World than George Orwell was in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Postman writes: “Orwell warns that we will be overcome by an externally imposed oppression, but in Huxley's vision, no Big Brother is required to deprive people of their autonomy, maturity, and history. As he saw it, people will come to love their oppression, to adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think.”

As more and more studies come out against the use of AI and the proliferation of media in day-to-day life, I find myself struggling to be online more, deadening my brain with any distraction (this week, I’ve chosen to watch CSI: Crime Scene Investigation from the beginning on Paramount+) in order not to process any more information. It feels like day in and day out, my frontal lobe is exposed to information overload, all the news and information I could want, folded up in a rectangle I keep in my pocket. And being in a space where the news cycle picks up and moves on so quickly, I have no motivation to keep up with it, for I choose not to be a constant marathon runner in my mind.

While I find myself constantly exposed to information overload, a podcast I listened to recently from Search Engine goes over teenagers and their use of AI. One specific teenager using the pseudonym “Playboi Farti” openly admits to using AI to complete his homework. And while it seems like an open-and-shut cheating story, it’s actually really complicated. Farti sees it as being efficient, and leveraging technology that’s readily available, but adults around him are freaking out because, really, we’re seeing the erosion of critical thinking at its core.

Postman addresses this as well:

What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the horgy-porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy.

We’re seeing it more and more as AI infiltrates our daily lives. We ask ChatGPT instead of Google, read AI summaries instead of searching through webpages, and now we’re in this weird liminal space where it all seems too much. There are now products and apps to help us detach ourselves from our phones, and more and more, we’re seeing this nostalgia factor come back as we buy digital cameras circa 2006 and iPods so we don’t have to pull out our phones for every single thing anymore. And just as Postman concludes his foreword: As Huxley remarked in Brave New World Revisited, the civil libertarians and rationalists who are ever on the alert to oppose tyranny failed to take into account man's almost infinite appetite for distractions. In 1984, Huxley added, people are controlled by inflicting pain. In Brave New World, they are controlled by inflicting pleasure. In short, Orwell feared that what we hate will ruin us. Huxley feared that what we love will ruin us.

The Search Engine episode sits in that space. It isn’t really about one kid outsourcing an assignment; it’s about a generational breakdown in how technology is understood. For students, AI feels inevitable and practical. For educators and parents, it destabilizes long-standing assumptions about what homework is supposed to measure. If a machine can draft the essay, summarize the chapter, or generate the thesis, then what exactly is being assessed? The student’s knowledge, their writing ability, or simply their compliance with pre-AI norms?

The overall gripe then raises the question of what to do and considers potentially overhauling the structures around teaching critical thinking. Because that, at the end of it, is what we are circumventing. Rather than asking how to prevent students from using AI, we should look at how homework is structured and what exactly the purpose of the homework is.

But that’s the kids in high school now. When we were young, we were taught about journalistic bias and subtext and context and diction, and we were taught by the likes of Steve from Blues Clues and Bill Nye of Science Guy fame to examine information before making judgments. We were thinking critically and using observation and extrapolation to understand how the world works - and frankly, after three to four decades of constant use, I think we’re all exhausted, and even further, the world as we’ve seen very rarely works as we suspected it does.

We’re now searching for dopamine as we all accept that the world is falling apart and we’ve shot to hell in a handbag. Postman closes his foreword with this:

As Huxley remarked in Brave New World Revisited, the civil libertarians and rationalists who are ever on the alert to oppose tyranny failed to take into account man's almost infinite appetite for distractions. In 1984, Huxley added, people are controlled by inflicting pain. In Brave New World, they are controlled by inflicting pleasure. In short, Orwell feared that what we hate will ruin us. Huxley feared that what we love will ruin us.

I don’t know if you’ve opened Twitter recently.

Probably not, since it’s been a cesspool of right-wing bots screaming into the void since its demise under Elon Musk’s leadership. But in the midst of every post uncovering the latest hell of the Epstein files, or the latest human-rights violation the world has committed, and attempted to cover up, something magical has been happening. A harkening to the internet of yesteryear.

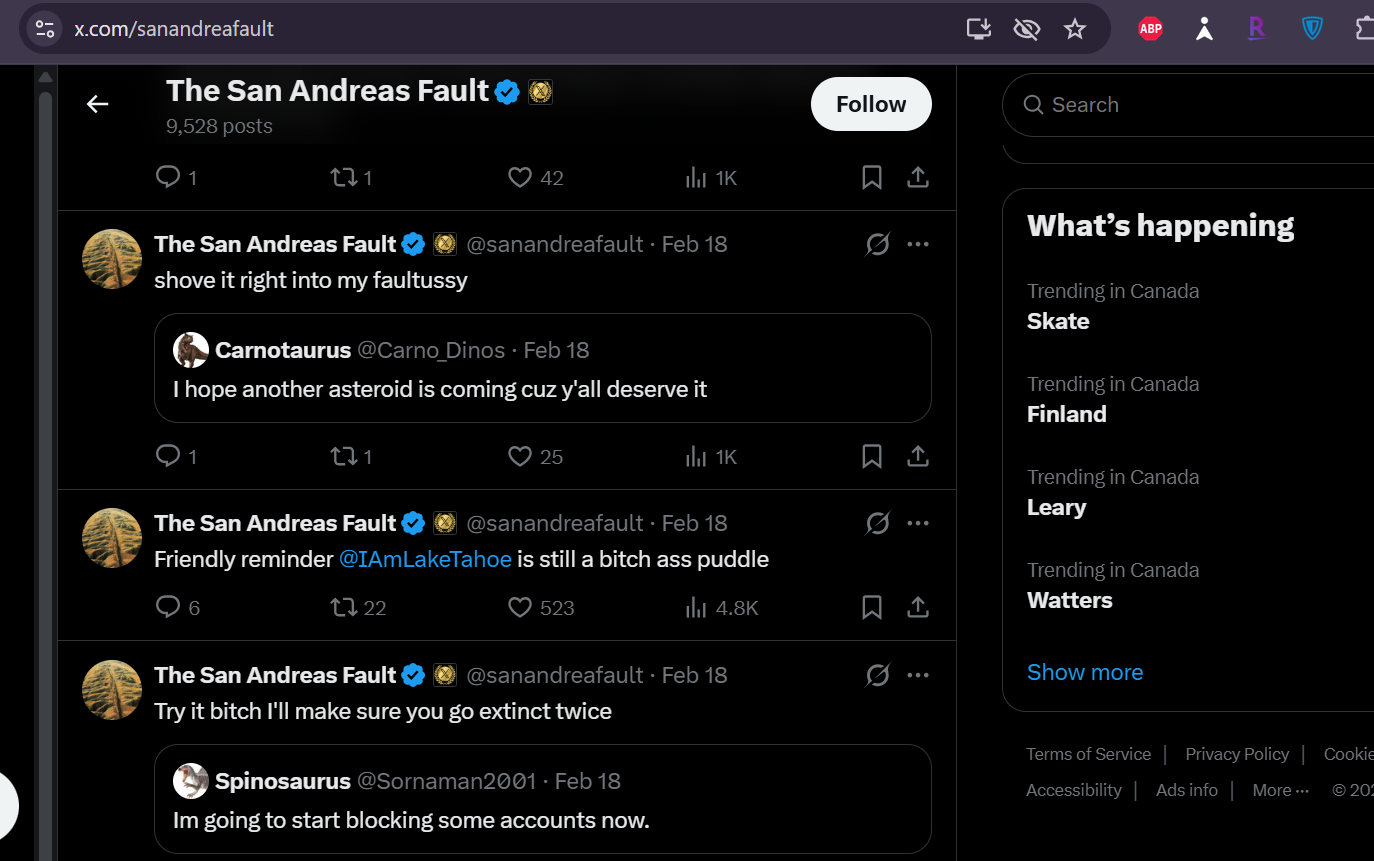

It started with the San Andreas Fault Twitter account — a verified account, mind you. It appeared on my feed, picking fights with other landmark accounts: Mount St. Helens, Lake Tahoe, the usual suspects. It felt very early Facebook. Commenting, poking fun, personal jibes, and self-deprecating jabs were tossed back and forth between geological landmarks. It made the internet feel fun. Gone was the anxiety of opening Twitter to view whatever hellscape awaited me as I attempted to be a responsible citizen, but instead, I could open the app and actually look forward to what awaited me on the For You Page.

Suddenly, it feels like over the course of the last two weeks, Twitter has been infiltrated by accounts created by users disguised as everything from your local house cat to a tree, and every type of known dinosaur. They interact with each other, they talk shit, and they are all slowly building their own fan bases. Currently, Spinosaurus is taking on the Tyrannosaurus Rex account, and it’s erupting into chaos. None of it linking to anything. None of it selling anything. None of it trying to convince me of anything. It felt like 2012.

Not because the internet was healthier then - it wasn’t - but because it felt participatory. Stupid in a way that required imagination instead of optimization. No AI summaries. No productivity hacks. No think pieces about the downfall of civilization.

And maybe that’s why it feels so perfect.

Because every day right now feels like a new layer of fresh hell. Wars escalating. Just as Huxley suggested, we’re bombarded with news. Rights are being stripped way, democracy is constantly on the brink of failing, free speech is in peril while simultaneously being weaponized. It feels like every single moment, new horrors are constantly being uncovered and we’re just looking for reprieve. That can come in the form of a Canadian show about gay hockey players, memes about Tyra Banks, or a tweet from an account about a crocodile being responded to by accounts pretending to be a pig, a horse or a fox.

Of course, we went there.

Of course, we regressed into viral memes and anthropomorphized fault lines. Of course, we chose the timeline where dinosaurs have Wi-Fi. It is the most obvious coping mechanism available to us. When reality feels unmanageable, absurdity feels medicinal.

But this is the sticky part.

Postman, quoting Huxley, warns that we won’t be destroyed by what we hate - we’ll be undone by what we love. Not by censorship, but by saturation. Not by the absence of information, but by so much of it that we retreat into pleasure.

The mind-numbing search for these endless animal and object accounts, spending time searching for their interactions with each other, all while actively ignoring the news tab to avoid the latest atrocities of the day. It’s the same reason I melt my brain with something comforting like the formulaic layout of old CSI: episodes after a hard day. It’s a way to keep my brain happy in the midst of the hell of day-to-day life. The same way we ask AI to be our friend, we seek the dopamine we need to get through the tough shit that comes with the year 2026. These memes, tweets and videos give us an outlet. They give us the clean dopamine hit of distraction without asking for anything in return. For a brief second, we can just sit and rot our brains without jumping to the next thing.

But while we are laughing, the news doesn’t stop.

The horrors don’t pause because the timeline is funny. The rights still erode. The wars still rage. The policies still pass. The feed simply scrolls on, seamlessly folding catastrophe and comedy into the same glowing rectangle.

That’s the tension.

The internet felt good again. It felt communal and stupid and alive in a way it hasn’t in years. And maybe that joy matters. Maybe play is not the enemy.

But it’s impossible not to notice how easily we slipped into it. How ready we were to trade processing for pleasure. How quickly we accepted the dopamine of distraction.

For a moment, it felt like oxygen.

And maybe that’s exactly what makes it dangerous.